ruins: phnom penh & siem reap travel blog

This is a bit of a different kind of travel blog. I wrote this from a riverside café in Phnom Penh, trying to savor the feeling of solid ground before a six-hour overnight bus ride, and process everything I’d just seen. This trip to Cambodia was kind of the grand finale of my time in Southeast Asia, but I also think it was the most important. To me, the primary purpose of travel is to learn. And I learned an immeasurable amount on this short trip.

Cambodia is a country I’ve wanted to visit for a while, given my temple obsession and the fact Gwendolyn always says it’s one of her favorite places in the world since she spent a summer there a couple of years ago. But I never thought that I would actually go, and I didn’t expect it to leave such a profound impression on me.

In the two days that I was in Phnom Penh, I learned about the Cambodian Genocide, something I’d never heard of until a couple of months ago. I’d only ever vaguely heard the words “Khmer Rouge,” and for some reason I can’t remember in what context. But I had never heard the horrific stories of this country’s recent past, and I was completely unaware of all of the events that unfolded, partly as collateral damage from U.S. involvement.

So this blog won’t be all fun. It still has a lot of food pictures and me nerding out over temples, don’t worry, but there’s also a lot of history in this one relevant to what’s happening now. Hearing these stories was an incredibly humbling and existential experience, and it reminds me that now more than ever, it is imperative that we learn from history, lest we repeat our mistakes out of arrogance in thinking it can never happen to us. But I hope you learn something from it too.

Disclaimer: I took around 1,200 pictures on this trip and only posted a very small portion of them and it’s still long, so grab a snack and a cup of tea, settle in, and prepare to take a virtual trip.

DAY 1: PHNOM PENH

I leave early afternoon for Phnom Penh. I’m excited, as I’ve been looking forward to this trip for quite some time.

Once I land, my first order of business is to get my visa. Despite being the fourth-poorest country in Asia and one of the least-developed countries in the world, Cambodia is not cheap—I paid $325 total for my plane tickets (more than the cost of my entire trip to Malaysia back in October), and a visa sets me back $33 USD.

Cambodia’s riel is a “closed currency,” meaning that you won’t find it at any money exchange places outside of the country, but they also accept USD, so I pay the $33 and then I hunt around for a SIM card. I don’t have to go far, as there are several kiosks right outside of the gates. I walk up to one, hand the woman a $10 bill, and she takes my phone.

“Wasn’t it $5?” I ask when she’s finished.

She stares at me blankly. “Yes.”

“So can I get $5 back?”

“But you haven’t paid.”

“What?! I literally just gave you $10.”

I’ll spare you the details of our fight, but suffice to say, very loud arguments are highly effective when it comes to scammers. She eyes me again, begrudgingly hands over a 20,000 riel note, and I’m on my way.

A tuk-tuk driver finds me right outside the airport (as in Thailand, you don’t hail tuk-tuks or taxis; they hail you), and he takes me to my hostel. The first word that comes to mind is...dusty. It’s got a similar vibe to Thailand and Malaysia, but somehow it’s all its own. It’s Chinese New Year, and the smoky-sweet smell of incense is everywhere.

There are more motorbikes and tuk-tuks on the road than there are cars, and lanes (and even roads) are a bit optional. Motorbikers with shiny, mirrored helmets speed past us, and simply go up onto the sidewalk when the roads get jammed.

The streets are lined with leafy, overgrown trees and neon signs, with thick, messy bundles of black cables hanging over the intersections like canopies. Children sell gasoline in Coca-Cola bottles to passing motorcyclists. I feel ridiculously extravagant with a $100 bill tucked in my wallet, which could probably feed a family of five for a week.

The Share Phnom Penh Hostel looks like a hipster coffeeshop, with an espresso bar and gelato display at the reception desk. The receptionist is the third person since I stepped off the plane to try to speak to me in Cambodian. “You just have that kind of face,” he explains, gesturing. And looking around, he’s right. Tanned skin, high cheekbones, flat noses, and thick, dark hair. It’s very strange to be in a country that is not your home country or your country of ethnic origin, a place that feels so foreign to you, and to be surrounded by people that look like you.

I drop my stuff in the room. It’s similar to the Matchbox Hostel in Bangkok, eight little bed capsules with curtains for privacy. This one is dark and made of concrete, but it’s equally as clean, which I like.

The driver is nice enough to wait around while I check in, and afterward immediately takes me to the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum, just before it closes.

Gwendolyn recommended this place when I asked for suggestions of what to do. “It’s not glamorous or anything,” she told me. “But it’s important.”

I am glad I came here. It’s not fun; in fact, it’s probably the worst thing I’ve ever seen in my life. But I think it’s good to feel sad sometimes. It means that we retain our capacity for shock and outrage, that we can learn something from the demons of the past. It means we do not feel nothing.

There are few places I’ve gone in my life where I’ve stepped inside and immediately felt overwhelmed. But this is one of them. Sometimes I have to stop and take breaks simply because what I’m seeing is too difficult to process.

I‘m not writing this because it makes good travel blog material. In fact, I’m sure it's much less appealing than pictures of Angkor Wat. But I’m writing this because it's a key part of understanding not only the country’s history, but also the absolute necessity of the protection of human dignity, something that has been highlighted in the wake of our new administration’s destructive and oppressive policies. I think I have a responsibility to share what I’ve learned. And I’m writing it because unlike the Holocaust, the story of the Cambodian Genocide isn’t familiar to most people. But it still deserves to be told.

Tuol Sleng means “poison hill,” and it’s actually a former school, used by the Khmer Rouge as a torture and execution center, one of many in a secret network of prisons and codenamed “S-21.” It looks like any other school, five tall concrete buildings surrounding a grassy courtyard. But this is not just a memorial. This is the actual place where tens of thousands of people were brutally murdered. UNESCO has registered it as “valuable to all humankind for its inhumanity.”

For context, this happened in 1975. This happened just 42 years ago, 30 years after the atrocities of the Holocaust had occurred and the world was presumed to have learned its lesson. Several of the people responsible are still alive today and were only recently on trial, and many of the survivors are only in their 80s.

Approximately 20,000 prisoners were held in Tuol Sleng. There are only twelve confirmed survivors.

There’s a lot of history behind the Cambodian Genocide, as it was a byproduct of the Vietnam War, but that’s another story. One of the saddest parts of the genocide was that there was no war. The war was already over. This wasn’t an offensive attack with the intent to kill enemies. This was a slaughtering of innocents, with the intent to completely eliminate any kind of opposition to the authority.

The Khmer Rouge (Khmer = main ethnic group of Cambodia, rouge = color of Communism) were established in 1968 as a foil to the sitting prince’s regime, and captured Phnom Penh in 1975. They instituted a radical program to ensure a truly “pure” and equal state, isolating Cambodia from all foreign influences, outlawing religion and currency, and promoting agricultural labor. Pol Pot, the leader of the regime, wanted to create a state of “agricultural communism,” so all books were burned and the intellectual elite murdered. He called it “the Communist Party of Kampuchea” or “Democratic Kampuchea” (DK). The audio tour describes it as “a vision for remaking society that destroyed our country.” Essentially, it was to fulfill Pol Pot’s twisted dream of a utopia, to eliminate class differences and start from Year Zero. An estimated 1.5 to 3 million people were killed in the course of the Khmer Rouge’s three year, eight month, 20-day rule.

I am in a room full of pictures. Of Pol Pot, of leaders of the Khmer Rouge, of cadres (soldiers). I am struck by how normal they look, these people that killed and gutted without hesitation. The soldiers especially. Some are smiling in their portraits. The oldest are in their early 20s, the youngest are only boys. They were easily manipulated and told that the DK was the soul of the country, filled with lies about “the ruling elite,” but many of them would later become prisoners themselves.

Once people were arrested, a process of dehumanization began. They were stripped of their clothes, given metal tags with identification numbers, and from that time on, were called only by their number and referred to only with gender-neutral pronouns. The goal was to break down their memory and coerce them into giving confessions, which would then be used against them.

Families were arrested all together, even children, in accordance with the popular Khmer Rouge slogan: “When weeding, pull out by the roots.”

Another room, this time with photos of the victims. It’s just walls and walls of black-and-white portraits, of grim and pleading faces. The classrooms are divided into tiny cells, like for cattle, with metal loops to shackle prisoners. Barbed wire netting covers the balconies, strung up to prevent prisoners from committing suicide. Visitors sit on benches in the courtyard, listening, stone-faced, to the terrors being described by the audio guide.

It is nothing short of horrifying to walk where blood was once spilled, where the stains on the floor are evidence of people dying terrible deaths. The air is stale and heavy. You can practically feel the weight of it smothering you. My throat is tight the entire time I walk through. I am standing in a place where people were murdered, secretly, in cold blood.

One of the rooms is a tribute wall to the victims. One message stands out to me: “Dear America, this is what happened when someone tried to ‘make Cambodia great again.’”

Germany, appalled by the tragedy and feeling deeply for Cambodia following the nightmare of the Holocaust, sent funds to help build this memorial. The German Ambassador at the time said in a speech:

It reminds us to be wary of people in regimes who ignore human dignity. No political goal or ideology, however promising, important, or desirable it may appear, can ever justify a political system in which dignity of the individual is not respected.

Of all the awful things in this place, one of the worst is a picture of one of the survivors at the hearing of Case 002 in 2012, the trial of the four surviving leaders of the Communist Party of Kampuchea. This survivor has spent most of his life educating others about the Cambodian Genocide, after his wife was killed and he escaped.

But to this day, none of them admit to their crimes, and instead blame their constituents. Two of the leaders died before they could be sentenced, one was declared mentally unfit to stand trial after developing dementia, and the last, “Duch,” the chairman of S-21 was sentenced to life in prison.

In response to the survivor’s testimony, Duch replied, “I would like to have responded to your wishes, but it was beyond my capacity because this work was done by my subordinates. I would presume that your wife was killed at Choeung Ek. Meanwhile, to be sure, I would like to suggest you kindly ask Comrade Huy who may know more details about her fate.”

I think it’s the cruelest kind of torture in the world, to confront the man that murdered thousands, including your family, and to watch him claim no responsibility whatsoever. It absolutely rips my heart to pieces.

The four leaders were charged with genocide and crimes against humanity. I’m surprised they have a fair trial process at all; it amazes me that these people were treated with such humanity when they themselves completely disregarded it. But I suppose that’s what makes the rest of us better than Nazis or the Khmer Rouge.

Afterward, I’m feeling very...heavy. I don't know any other way to describe it. I need some time to just kind of be by myself and think, so a tuk-tuk driver takes me to the riverside. I walk by the riverside and watch the boats sail into the sunset. It’s gorgeous from here, all cotton candy and sherbet colors. One of my favorite things about sunsets is that they look beautiful in every city.

I wander down to a lighted temple. Crowds of people clamor around, offering bundles of flowers and incense to the states of Buddha. People buy tiny brown birds in cages to set free, and bags full of water with flowers in them to splash on their faces.

Alongside the river are a bunch of restaurants and bars. There are an odd number of pizza places in this country. The biggest chain is The Pizza Company, which was actually pretty highly recommended, but I can’t bring myself to eat pizza in a foreign country, unless it’s Italy.

The smaller pizza restaurants also serve traditional Khmer food, so I sit down and order lok lak, a beef dish that I’ve actually heard of (the power of brand recognition), and an Angkor beer. The bottle is huge, and it’s only $1.80. It tastes like Chang beer, if I remember correctly. I’m not wild about it.

The lok lak is good. I’m not even quite sure how to describe the taste...it’s salty, but with a tinge of sweetness (I later find out it contains oyster sauce). It’s like nothing I’ve ever had before, but somehow it doesn’t really taste foreign.

I realize this is my first meal of the day and I’m a bit buzzed by the end of it. My hostel is right down the street so I walk home. It’s only 8:30 pm (9:30 pm Singapore time) but I quickly fall asleep.

DAY 2: PHNOM PENH

I wake up and call the same tuk-tuk driver, the one that picked me up from Tuol Sleng. He offered to take me to the Killing Fields, so now he pulls up and I hop in, settling in for a long ride.

Away from the dust of the city, Phnom Penh is strikingly pretty—a huge stretch of land, with smooth blue water in the middle of a tangled mess of greenery and colorful buildings dotting the edges. It looks very developing country now, with crumbling brick buildings surrounded by landfills and lots of overgrown trees.

The Choeung Ek Genocidal Center is one of 300 “Killing Fields” in Phnom Penh, or a mass grave. There’s a sheltered pit, where 450 bodies were discovered after the regime ended.

During the Khmer Rouge regime, 80% of Cambodia’s population lived in poverty, in part from American bombings of Northern Vietnamese supply lines. Pol Pot praised the “common people” and wanted to eradicate everyone that could undermine him. He saw intellectualism as a threat, and the source of class wars. These “New People” were enemies of the state. He built his army from young, uneducated boys and men, teaching them that the wealthy were evil and responsible for the suffering of the poor.

In the first three days after the takeover, the Khmer Rouge cleared out the entire city and sent everyone to “collective labor camps.” The goal was a completely self-sufficient society, so rice production was demanded to be tripled, an impossible task. People were worked to death, and those who didn’t meet the DK's ludicrously high standards were sent to the Killing Fields.

Nine Westerners were also killed here: one Australian, two French, and six Americans. No one knew what was happening, because the borders were all closed with landmines and only diplomats were allowed across. It was completely isolated from the rest of the world.

I look at this place, this now-beautiful place where so much ugliness occurred and fragments of bones, teeth, and clothing still float to the surface years later. It’s terrifying to think how easily humans are controlled by fear, and what awful things we are capable of when fear is the motivator.

Amazingly, these places were kept secret, and the people working nearby were unaware of Choeung Ek’s existence until it was discovered much later. No guns were used, as the sound would have attracted attention. Instead, soldiers used machetes and blunt objects to brutally tear apart their victims.

There is a large tree, called “The Killing Tree,” its roots gnarled and its branches forming a canopy over a pit. Soldiers would smash babies’ heads against it and toss them into the pit, all while playing revolutionary music to drown out their cries and the moans of the other prisoners.

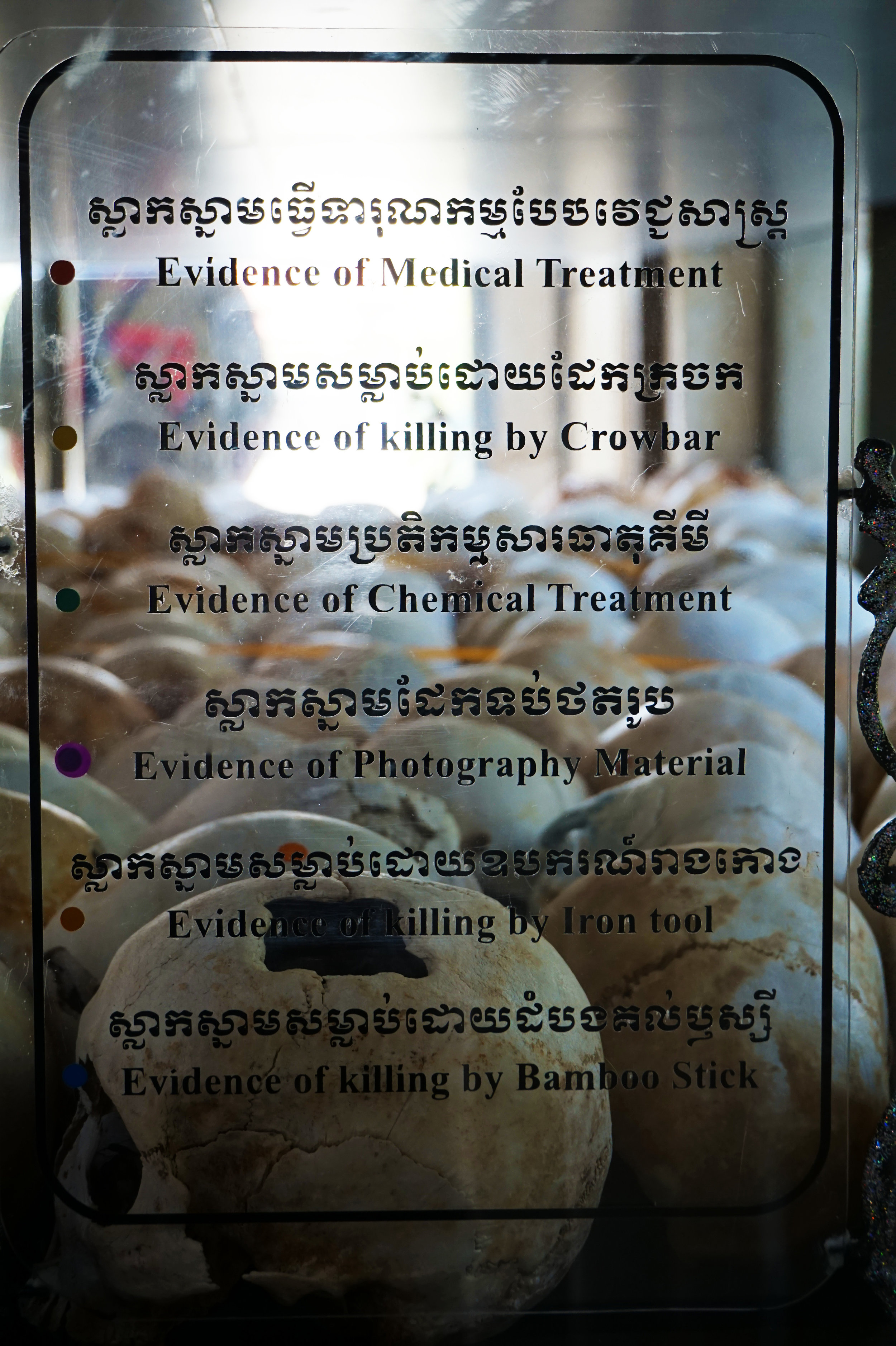

At the end of the tour is the stupor, a towering pagoda-like structure that houses hundreds of skulls in a large glass case stretching to the ceiling. The skulls are labeled with colored stickers, indicating how each victim was killed, like a grotesque museum of death.

I’m glad I came here too. I think it’s a good thing to confront ugliness; in fact, I think everyone should be required to see things like this, to fully grasp the potential consequences of the political rhetoric they’re endorsing.

I meet my driver again. I’ve decided I like tuk-tuks because for some reason they don’t make me carsick. He takes me back to the city, to Wat Phnom, one of the major temples in Phnom Penh, to observe Chinese New Year customs.

It is absolute madness. Hundreds of people crowding the altar, kneeling in front of Buddha statues, offering flowers, incense, fake $100 bills, and even plates of raw meat. The incense overflows, piles of it covering the floor like hay at a petting zoo. I am jostled around a lot and all of the smoke is making me quite dizzy, so I get the heck out of there.

I consider touring the Royal Palace but it’s $10, which is kind of a lot, and palaces don't interest me all that much, so instead I walk back to the riverside to eat.

It’s only after I finish that I notice all the street carts selling noodles for $1.50 on the way back to my hostel. Damn. I grab my things and grab a tuk-tuk to the Phnom Penh Night Market, where the night bus station is, to walk around a little bit before I leave for Siem Reap.

I guess I’m a pretty unexciting person, because one of the craziest things I’ve done in my life was book the tickets to Phnom Penh and from Siem Reap, without a plan to get from the former to the latter. But I did some research and found Giant Ibis, a trusted night bus company that takes travelers between provinces for $15.

It’s just a bus full of beds, what I imagine the Knight Bus from Prisoner of Azkaban would look like (no hot chocolate or toothbrushes here, though). You get a blanket, a pillow, and a bottle of water. Because the trip is at 10:30 pm to 5 am, this is pretty much my hostel for the night. It’s surprisingly comfortable, in part I suppose due to the speed limit, and I manage to sleep for a bit.

And then I wake up hungry at 2 am. I wish I’d eaten more than boba at the night market.

DAY 3: SIEM REAP

I arrive in Siem Reap at 6 am and I immediately take a tuk-tuk to Angkor Wat, because the best times to see it are sunrise and sunset. Probably the second-craziest thing I’ve done in my life, as I’m running on very little sleep.

The sky is layered in dusty purples and oranges. It’s freezing and my teeth are chattering, but I have a stupid grin on my face the entire time because I’m so excited. The sleepiness has completely gone and is replaced with pure exhilaration.

The tuk-tuk driver charges me $15 from the bus stop, which is outrageous, but the sun is quickly coming up so I hand it to him and run inside. The pictures don’t even do it justice.

Angkor Wat was originally a Hindu establishment, but was converted into a Buddhist one in the 16th century. It’s not actually a temple (or at least not just one temple), but an entire complex of many temples. The name literally translated means “City of Temples.”

I was right to come early. By the time I leave at 8:50 am, the place is crawling with tourists. I am determined to wake up early enough to be there at the opening at 5 am at least once this trip.

Much of it is weathered away, but it remains as magnificent as ever. When you stand on the steps of Angkor Wat, you’re immediately struck by how big it is, and you become fully aware of how it towers over you and stretches further than your eye can see. In fact, this is the largest religious monument in the world, and it’s breathtaking.

This is like peak temple exploration. Nothing I ever see in my life will compare to Angkor Wat, temple-wise. I love how the temples here are so well-preserved, but you’re still allowed to wander around in them, and they remain mostly untouched. They’re not as neat or as perfect-looking as temples in other countries; they’re wilder, with the weathering of time plainly on their faces, but I like that. They’re much more rustic, yet somehow still sophisticated. I like that the Cambodian people have allowed nature to take its course and kind of let them be.

I get back to the hostel, thoroughly exhausted from only having slept around three hours, and then running around a temple at 6 am (it’s now 9 am). But I’ve never been happier. The Missing Socks Laundry Café is the cutest hostel I’ve been in yet. It has an actual café downstairs, so a lot of people stop in for coffee, and there’s a little porch outside with a bunch of washers and dryers where people can do their laundry.

The upstairs is so clean and airy. I’m happy I chose this place to spend three days. I unpack, take a shower, take a nap, and then I take another tuk-tuk back to Angkor Wat.

This time I go to Ta Prohm, which looks straight out of an Indiana Jones movie.

It’s kind of hidden away; you have to walk a long dirt path through the forest just to reach it, and it’s shaded by massive trees, whose roots have now broken apart many of the walls and twisted over towers. I imagine this used to be a very nice to worship, alone, in silence. This is apparently where Tomb Raider with Angelina Jolie was filmed, which is pretty cool, and it actually caused a sharp increase in tourism in Siem Reap after that.

From Lonely Planet:

Built [in] 1186 and originally known as Rajavihara (Monastery of the King), Ta Prohm was a Buddhist temple dedicated to the mother of Jayavarman VII. It is one of the few temples in the Angkor region where an inscription provides information about the temple’s dependents and inhabitants. Almost 80,000 people were required to maintain or attend at the temple, among them more than 2,700 officials and 615 dancers.

It’s a little too early to call, but I'm going to go ahead and say that this is my favorite temple in Angkor Wat. It’s just...perfect. The architecture is otherworldly, like living inside a fairy tale. After it was abandoned in the 15th century, it was left to fall into ruins.

It’s full of high, crumbling towers and shadowy corridors, and you can see where the limbs of the trees have crept up the intricate stonework, slowly overtaking it and crushing it over time. Somehow, the destruction makes it even more beautiful, like a magical mix of art and nature, with the temple actually becoming part of the jungle over time, disappearing into the place from which it was born.

I am always in awe of hand-carved things, like Greek statues or bas-relief, because I think it’s incredible that people could create such intricate things by hand. I can’t even imagine having that kind of patience and focus. A lot of the carvings here are intact, so you can still see many of the details, even 800 years later.

My tuk-tuk driver promised to wait for me at the entrance. Unfortunately, I got lost and am now at the exit, with no way of contacting him, and the security guards won’t let me go back in because the temple is closing. A tuk-tuk driver offers to take me around to the front...for $2. No thanks. So I begin walking. One of the temple security guards pulls up on a motorcycle.

“You need a ride?” he asks. I answer no, I’m just going to the front of the temple. “I can take you,” he offers. I tell him I don’t have any money but he shakes his head and says he’s going that way anyway. This is slightly suspicious so I tell him I’ll walk. He laughs. “It’s around 2 km around the whole thing,” he informs me. I could walk 2 km. But my tuk-tuk driver is waiting and I feel bad. “Okay,” I say, hoping I don’t get murdered or fall off, thinking, My parents would absolutely kill me right now (third-craziest thing I’ve done in my life). But it’s actually exhilarating. I kind of want to learn how to ride a motorcycle now.

Luckily, I make it back in one piece, and my driver and I are on our way.

I go back to the hostel, change, and hit the night market. Another great thing about The Missing Socks Laundry Café is that it's right in the middle of everything—there are bars and restaurants and hostels lining the streets, and a night market right around the corner. I go off in search of food and venture over to Pub Street, which is known for being a prime bar-hopping location and has a lot of local food carts for late-night snacking.

The “fear factor” ones are everywhere, the ones with tarantulas, scorpions, and cockroaches. You see them a lot in Thailand too, and they make you buy something before you can take a picture of it. I know for a fact that ants are part of Khmer cuisine, because Gwendolyn was offered some when she was there, so although these particular ones are tourist traps, eating bugs may be more commonplace here.

I meet Ujy, Joseph, and Myka from the Philippines, also fascinated by the bugs, and we share a tarantula. It tastes good, but the texture is a bit like eating shrimp in the shell, with less meat.

Ujy is a photographer, Joseph is a hiker, and Myka is a blogger (you should check out Ujy’s and Myka’s work; they’re both amazing!). The three of them are also on vacation, but they’re seeing three countries in just seven days. They arrived earlier today on a bus from Bangkok, and they’re going to Phnom Penh tomorrow, and Ho Chi Minh the next day.

We find a free traditional Apsara dance show at this rooftop bar, which was highly-recommended by a lot of travel sites. It’s a lot like the ones in Thailand: elaborate headdresses, rhythmic drumbeats, and very deliberate movements.

Afterward we go off in search of food. We find pancakes, which are basically the Cambodian version of roti prata, and we try traditional Khmer amok, fish in coconut curry sauce.

I get a pineapple smoothie and Ujy and Myka get fresh chai tea. We drink them by the river and watch the lights dance in the water, listening to the sounds of the night market. It’s pretty crazy that I only just got to Siem Reap this morning. It seems so far away.

We walk the streets and find this little shop selling retro-style movie posters and oil paintings. Ujy is ecstatic to find a whimsical rendering of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and I fall in love with a minimalist painting of the Bayon Temple. It’s on a wooden frame and will be difficult enough to carry back to Singapore, let alone the U.S., not to mention it’s for the apartment I don’t yet have, but it’s too pretty and I end up buying it.

We make a plan to meet up at the Bayon temple at Angkor Thom tomorrow morning, and we say goodnight.

DAY 4: SIEM REAP

I wake up early and eat breakfast. The hostel provides free breakfast, another perk; the chef makes me the best waffles I’ve ever had in my life, topped with mango and drizzled with honey, and the barista makes me one of those fancy cappuccinos with the latte art on top.

Once I’ve finished, I take what seems like the millionth tuk-tuk of this trip back to Angkor Wat.

Did anyone else play the computer game ClueFinders when they were younger? The faces kind of remind me of the stone guardians in the Rings of Fire puzzle of “The Mystery of Mathra” and I pause for a moment at the absurdity of me making ClueFinders references in the middle of Cambodia. But they look so serene, and they appear to smile knowingly. Apparently, they’re often called “the Mona Lisa of Southeast Asia,” and there are four of them on every tower, keeping watch at every compass point. This temple stands at the middle of Angkor Thom’s four gates, and represents the intersection of heaven and earth. The faces have fallen and cracked with time, but they’ve been carefully restored and now have a gorgeously weathered look.

There are two large “libraries” on either side of the East Gate, and you can actually climb a steep staircase to the top. I would not have worn a skirt today had I known there was this much climbing involved. But it’s awesome. You can see everything, the crisp outlines of the faces where they’ve cracked and moss has grown, the full splendor of the whole sanctuary, all of the columns reaching skyward.

Still no sign of them. They don’t have SIM cards, and I don’t have signal or wifi to message them. I suppose this is what happened before people had smartphones. It’s 10:30 now, so I leave the Bayon and go off in search of the Baphuon temple.

I end up just wandering, because that’s what I tend to do when I’m alone, and there’s certainly no shortage of temples here. The Baphuon was dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva, another example of mixing Buddhist and Hindu ideology after the conversion, and much of it has collapsed, as restoration efforts were interrupted by the Khmer Rouge takeover. Hidden by a grove of trees with two glassy lakes on either side, it looks like a Baroque painting.

Afterward, I find a little outdoor restaurant that’s full of tourists, and order some noodles for lunch.

I’m sleepy now. And it’s 1:30 pm, one of the hottest hours of the day, so I have no desire to be in the sun, but I do want to be back at Angkor Wat for sunset. What I really need is a nap right now, and I contemplate my next move. I take a tuk-tuk back to Angkor Wat, and sit in the window of one of the outside buildings, watching the crowds of tourists pour into the main temple.

I finally have signal, and I get a message from Joseph: “We're at a café in front of Angkor Wat!” I meet them at the café, where we have ice cream to cool off for a bit before going into the temple. As it turns out, they were at the Bayon this morning too, but for some reason we missed each other.

We go back inside and marvel again at the fantastic architecture. Joseph and Ujy go off in search of some good angles of the stairs to photograph, and Myka and I meet a monk, who offers blessings in the form of a short chant and a string bracelet.

We meet another group of monks outside of the temple. They agree to take a picture with me, but insist that I stand a certain distance away, to preserve dignity. I agree out of respect, although I can’t help but feel the sting of misogyny.

Personally, I think Angkor Wat, for being the namesake of the complex, while gorgeous, is the least interesting out of the temples. Besides the entry façade, there’s not a lot to see; instead, we just wait for the sunset.

The three of them have to catch the night bus, so I go back to Pub Street alone, which is as vibrant as ever. I try Khmer-style soup, which turns out to be very similar to pho, but with rice instead of noodles, and approximately three times the cilantro (if you read my Thailand post, you know how I feel about that). It’s good once you get past the bite of the cilantro, but I’m still not a fan. The avocado smoothie, on the other hand, is excellent. It’s amazingly creamy and a little sweet, and why haven’t I used avocado in more of my baking? I immediately start Googling recipes.

Then I go back to the hostel and sleep, because tomorrow is my last day in Cambodia and I will make that sunrise at Angkor Wat or die trying.

DAY 5: SIEM REAP

I wake up at 4:45 am. It is much too early and I hate everything. My tuk-tuk driver is waiting on the corner, as promised, and we’re off. It’s pitch-black outside, but I’m surprised by how alive everything is.

Some of the outdoor markets are open already, and people are already cooking in their street carts in the hazy, blue-white glow of fluorescent lightbulbs.

My driver drops me off, and I join a sleepy procession of tourists shuffling into Angkor Wat. We still can’t see anything; the only light is from our phone flashlights. I claim a spot by one of the ponds, where I can just barely see the hazy outline of Angkor Wat start to appear in the water.

The sky goes from navy to cerulean to pastel orange and pink, and I don’t regret waking up early anymore. Now I can say I did this at least once in my lifetime, and that I can finally cross “watch the sunrise at Angkor Wat” off my bucket list.

I finally get signal and see an unopened message from my friend Vahan, who is studying abroad in Hong Kong and just happens to be in Cambodia at the same time I am. He was supposed to get in from Phnom Penh at 6 am this morning, and it’s 6:30 am now.

“Sorry, I didn’t see this! I’m at Angkor Wat rn,” I message him.

”Wait, me too,” he replies.

As it turns out, he and a bunch of his friends did the same thing I did on my first day here—went straight from the bus to Angkor Wat to catch the sunrise. I meet him at the gates (how cool is that...meeting up at an iconic site on the other side of the world), and we get breakfast at a little café outside of the temple. He and his friends are all hilarious and a lot of fun, just a group of guys traveling from HKU together. It makes me miss my friends more than ever.

The last thing I do is I check out of the hostel and head to the Old Market, which is where the local population goes to shop. It’s quite a sight: a giant warehouse full of tables where people sell piles of meat, baskets full of vegetables, whole fish, and packets of spices.

I’m awful at haggling. The absolute worst. I’ve found that silence is the best bargaining tool in any kind of business, whether it’s getting more information from people or getting a better deal at a market, which works well for me because I’m pretty comfortable with silence. But once you hesitate and they quickly offer a lower price I always feel so bad, because this is their livelihood and they’re so desperate to make the sale. So I usually pay the second price, no matter what it is, because I figure a couple dollars is worth a lot more to them than it is to me. It also means that I always end up spending more than I need to.

And with that, I’m on my way back home to Singapore. Only two more weeks until I leave for good.

I mentioned before that this was a different kind of travel blog post, and one of the reasons is that it comes with a warning for our country.

I appreciate that I saw Tuol Sleng and the Killing Fields at the beginning of my trip, because it provided me with a lot of necessary context; my experience was framed by the history of it all. And I really do think it’s important. It helps you understand the people a little bit more. It makes you marvel at the resilience of the human spirit, at the way Cambodian people are still so kind and welcoming despite losing an entire generation to a massive tragedy and being subjects of unspeakable cruelty.

The most terrifying part of the Cambodian Genocide is that it’s so fresh. It happened at a time when disco was still in fashion, the year the Pittsburgh Steelers won the Super Bowl and the Warriors won the NBA Championships, the year SNL went live for the first time, and the year the laser printer was invented. While America was ushering in a new era of peace and progress, building a stronger country, Cambodia was falling apart.

It began with a man who studied media technology and was a teacher. A regular guy. The people he recruited were normal civilians, those who were struggling to survive and blamed the wealthy for their plight. They murdered their own neighbors, convinced they were doing the nation a service of ensuring ideological purity.

And we see it happening now. Citing the “educated elite” as the enemy. Eliminating foreign dependency via isolationism. Creating a registry of people, assigning them numbers instead of names. Cultivating fear and hatred and distrust, citizen against citizen. It’s happening in our country. This is exactly how the Cambodian Genocide began. This was not the Holocaust or the Rwandan Genocide, where they were selective by ethnic group. This was a power move, to get rid of everyone who was perceived to be in disagreement with or against the ruling power. No one believes it can ever happen to them, Cambodia included. But if our administration continues the way it is going, it can easily and rapidly devolve into something worse, and there are very real repercussions for the chaos and damage our government is causing right now, and the authoritarianization that is occurring.

I don’t think it can reach the point of genocide, as we are a much more developed nation than Cambodia, but a 1984-esque scenario is entirely possible, and in many ways is our reality right now: one in which Americans live in fear, in which the government feeds the masses twisted propaganda to convince us that we are at war with an invisible enemy, in which facts are relative or inconsequential and strictly controlled by the ruling party. And I am afraid, not because of what will happen to me, but because of what will happen to the culture of our country, to our socioeconomic and geopolitical status, to our people. I am afraid of what will happen to those that weren’t born into a middle-class American family like I was. I write this as I watch videos of actual neo-Nazis celebrating our president, as he signs executive order after executive order stripping away our human rights, as he openly lies to the public, threatens anyone that disagrees with him or his administration, and walks back his promises. We cannot be boiling frog victims. We have to know when our standards for basic humanity and compassion are being lowered.

The audio tour of Tuol Sleng ends with a final plea from one of the survivors:

When you leave here, you will return to your normal life. But that is not true for the thousands of people that came here ... Tell others what happened so that we may strive for peace, compassion, and human dignity everywhere. There is still work to be done.

It’s been eighteen days now since I left, and still it echoes in my head.

RULES FOR PRISONERS AT TUOL SLENG

1. You must answer accordingly to my questions...don’t turn them away.

2. Don’t try to hide the facts by making pretexts this and that, you are strictly prohibited to contest me.

3. Don’t be a fool, for you are a chap who dare to thwart the Revolution.

4. You must immediately answer my questions without wasting time to reflect.

5. Don’t tell me either about your immoralities or the essence of the Revolution.

6. While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all.

7. Do nothing, sit still and wait for my orders. If there is no order, keep quiet. When I ask you to do something, you must do it right away without protesting.

8. Don’t make pretexts about Kampuchea krom in order to hide your jaw of traitor.

9. If you don’t follow all the above rules, you shall get many many lashes of electric wire.

10. If you disobey any point of my regulations you shall get either ten lashes or five shocks of electric discharge.